On Spirituality

30 On Purpose: April

It’s time for April’s ‘30 on purpose’ essay; and as it’s a pretty long one this week I’m going to skip including the usual bundle of links to start us off.

I was all ready for this month’s 30 on purpose to be about neurodivergence - about coming to terms with the way my brain works and learning to (mostly) work with it rather than against it. I was going to use the book event with

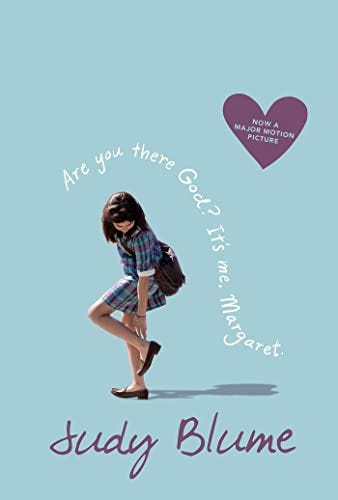

at Topping’s this Monday (part of the promotion for the paperback of her newest book, Enchantment*) as a jumping-off point; a previous book of hers, The Electricity of Every Living Thing* is as much an exploration of what it is to be a late-diagnosed autistic woman as much as it is an account of walking the South West Coast Path. (*all book links in this post are Amazon affiliate links)And then I read Enchantment* and watched the film of Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret* and realised what I really want to talk to you about this month was spirituality.

One evening after work this week, I crawled into bed, unzipped my cross-stitch project bag, and opened the Prime Video app on my iPad. I’d worked two consecutive days in the office, hiding behind my noise cancelling headphones in an attempt to keep overstimulation at bay and get some work done. I’d got done what I needed to, but I was exhausted.

I cry a lot but I am so productive, it's an art

(Taylor Swift, relatable to stressed-out neurospicy people everywhere)

I’d vaguely intended to rewatch the film adaptation of Red, White, & Royal Blue*, but the carousel of films on the app’s homepage distracted me - especially, the title card for Are You There, God? It’s Me, Margaret*, the film adaptation of Judy Blume’s book of the same name.

Blume isn’t as ubiquitous in the UK as I believe she is on the other side of the Atlantic, or at least by the time I turned to the ‘teen books’ shelves in the mid-00s, she wasn’t. The shelves were full of books by Jacqueline Wilson and Louise Rennison, British authors writing similarly approachable and relatable fiction for girls in that tween-to-teen age group. So I don’t remember when I first picked up Margaret, but I think, most likely, it was the paperback copy in my high school’s library, pages darkened and made soft by age. I was the same age as Margaret is in the book - an eleven year old in a new school - and while I wasn’t caught between two religions as she is, I found myself halfway in and halfway out of religion.

My grandpa on one side - he passed away almost 20 years before I was born - had been a vicar. I’d grown up with religious traditions instilled in my by my grandmother on that side of the family; we used to go to her church every year for Mothering Sunday, and to one near my primary school for their Christingle service on Christmas Eve. For a short time, I’d bene in Sunday School, but all I remember is the heavy fabric of choir robes and church hall curtains, so I must have been pretty young; it may just have been the natural follow-on from the preschool playgroup in the church hall. I assume that my copy of The Book of Common Prayer had been my grandmother’s on this side of the family.

My grandparents on the other side - well, it’s fair to say that the only spiritual being they encouraged me to believe in was Father Christmas. Both in the Boy Scouts and later during his National Service, my grandad did anything he could to get out of churchgoing or weeding the churchyard. He just was. not. interested.

And so there I was, a serious, bookish, eleven year old, suddenly in a giant school surrounded by 1000 other tween- and teenage girls, some of whom looked like adults. I was all too aware of the ways in which the world was not the play-filled idyll of primary school; the London tube and bus bombings had happened that summer, and I’d gone from a friendly little school where music and sport were my headteacher’s twin passions (along with his runner beans!) to a girls’ grammar school with a Latin motto on its crest (what a pretension for a school founded in 1966!) and where academic achievement was to be prioritised above all else; we didn’t even have school plays. Play was not encouraged (I’ll come back to this next month, when I will write about neurodivergence!) So that slim paperback with a bewildered girl of my own age on the cover, searching for reassurance, seemed ideally designed for me.

The spirit of ‘30 on purpose’ as a theme is that I ought to be telling you I’ve figured this out to an extent by now, that I’ve reached some level of understanding that I’m taking with me into this new decade.

Nope.

In my early 20s, I was a fairly regular churchgoer, finding solace in the community and rituals, first during the headlong marathon of my final year of undergrad, and then during that first horrible winter in Edinburgh when I was a lodger in a flat of consiracy-theory-believing didgeridoo whittlers and working in a job that wasn’t a good fit at all.

I’ve kept the bits I liked most from my churchgoing habit - the emphasis on doing rather than on saying, for example. In my Edinburgh church, we had a ‘20s and 30s’ group who would go to the pub after services on a Sunday evening; I still consider some of this group to be among the best people I know. But I remember one of the other people there telling me that a religiously conservative (and vocally homophobic and sectarian) man was her MP where she’d grown up, and she thought he was a pretty good guy, actually. I couldn’t reconcile the views this politician spouts with the message of Christianity as I understand it - love and peace above all else. The message I took from the couple of years of churchgoing was the goal of becoming ‘Christlike’: humble, loving, patient, and kind. I can think of worse underpinnings for one’s moral framework.

“Talking to God does not require faith, but practice. It is a doing rather than a believing, an act of devotion” (Katherine May, Enchantment)

Since then, I’ve gotten out of the habit, but while religion is no longer so present in my life, spirituality is still important to me. With all this century’s uncertainties, it feels better to believe that there’s something out there to believe in (and I don’t care if that’s circular!). The examples of monastic life described by Sarah Wilson in This One Wild And Precious Life* sound deeply appealing (other than the vow of poverty - I love to be surrounded by nice things!). On Katherine May’s recommendation I’ve got Catherine Coldstream’s Cloistered* cued up on my Kindle - I’ll report back. But even without that formal religion, I have been developing my own rituals, my own ways to engage with and place myself in the world that I live in. I’ve even dipped my toe into the world of tarot, with a few decks that I like to consult when thinking about life’s big questions.

As May says in Enchantment, “Ritual is different from worship; a matter of instinct rather than construction, a gesture that lets us weave significance in the moment.”

More importantly, I think about the point of it all. For me, it’s faith - not faith in a deity, but faith in the future. As I’ve mentioned before, I work in climate policy and communications (and some reflections on that formed the bedrock of an Anne Helen Petersen post earlier this week which I encourage you to read). I went to an event earlier this week where some students asked me how I’d ended up in that job and why I do it. After recounting the somewhat wiggly path I’ve followed, I explained that - for me - it’s a sense of vocation. The climate crisis is indupitably an emergency. The world is on fire. And I have the skills to help - even if just a little - in putting that fire out. So therefore I have to do it.

Continuing to do that work without falling into a pit of despair relies on maintaining a sense of hope - even through gritted teeth - that we can do it. We can prevent the worst outcome.

“The alchemy comes in understanding the truth that is so easily hidden: that everything is interconnected. That there is only one whole. That we exist within a system that includes every degraded human act and every beautiful one, every blade of grass and every mountain; that shines and snaps and varies like the surface of the sea. We as individuals contain it all. We hold within us the potential for the greatest good and the most dreadful end. We know, intuitively, how each feels, because there are lines traced between us and everything else. I don’t have to believe in God as a person. I can believe in this instead; the entire mesh of existence binding us together in ways we perceive only if we listen. Each of us is a particle of this greater entity. Each one of us contains it all.” (Katherine May, Enchantment*)

I’d love to hear about how your relationship with spirituality and religion has changed as you’ve moved through life - or if it’s stayed constant, which is - to me - just as interesting.

Speak soon,

Lily

PS: The Amazon affiliate links above only works to give me commission if you click through from the Substack app or website, rather than directly from your email program. Other ways to support this newsletter include liking, commenting, and sharing it with a friend who you think might like it. Thanks in advance!